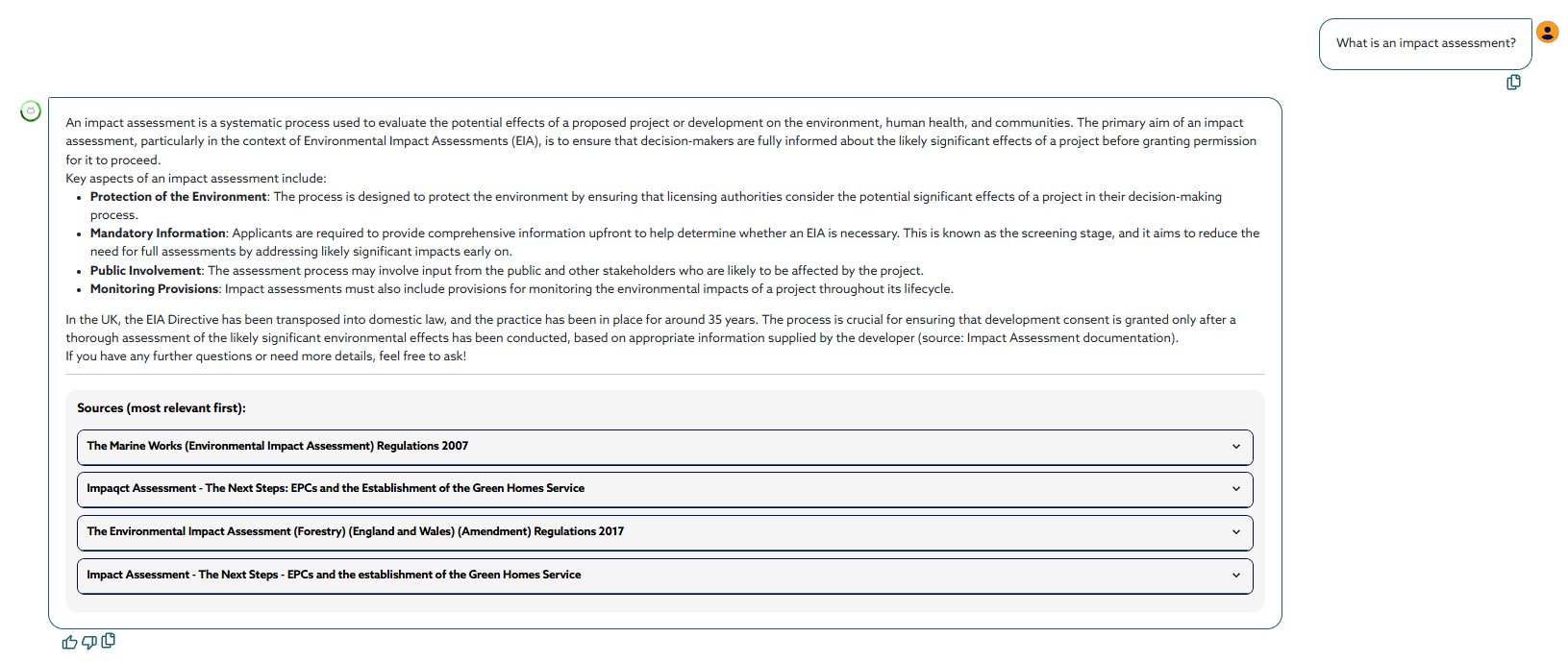

Building an Impact Assessment Assistant part 1: The problem and the RAG solution

My team recently launched an internal chatbot for colleagues to locate information from impact assessments and impact assessment guidance in a natural-language interface. As a technical lead on the development of this project, this is the first of three blog posts taking a deeper dive on the technical path that led us to deployment.

The problem

I’ve never had to write an Impact Assessment myself, but we knew directly from the expert economists who partnered with us on this project that they can be difficult to research and draft.

What is an Impact Assessment? As explained by our chatbot – it’s a systematic process used to evaluate the anticipated impacts of proposed legislation or regulatory measures. The primary purpose of an IA is to support the appraisal of new primary or secondary legislation by assessing the potential economic, social, and environmental effects of the proposal. We typically refer to an IA as the document capturing this process.

Efficiently retrieving knowledge from legislative documents—often spanning hundreds of pages on legislation.gov—is a significant challenge when researching for a new impact assessment, especially given the limited title-keyword search capabilities of the legislation.gov site. When niche impact assessment approaches are devised for niche policy areas, the lack of findability for these leaves analysts at risk of duplicating work or missing out on building upon previous efforts, undermining the overall possible quality of work. The current process relies heavily on the existing knowledge and experience of team members or seasoned colleagues, resulting in frequent, repetitive queries that consume valuable time which could be diverted elsewhere. Moreover, analysts without access to experienced colleagues or comprehensive records may end up conducting too narrow research, leading to missed opportunities for improvement. While tools like Google and .gov sites can help, they have their own biases and limitations, so the more search tools available, the better. These disparate, archival-focused data sources mean no tool exists that allows analysts to search across and within documents by actual content. This is the gap the chatbot addresses.

The RAG

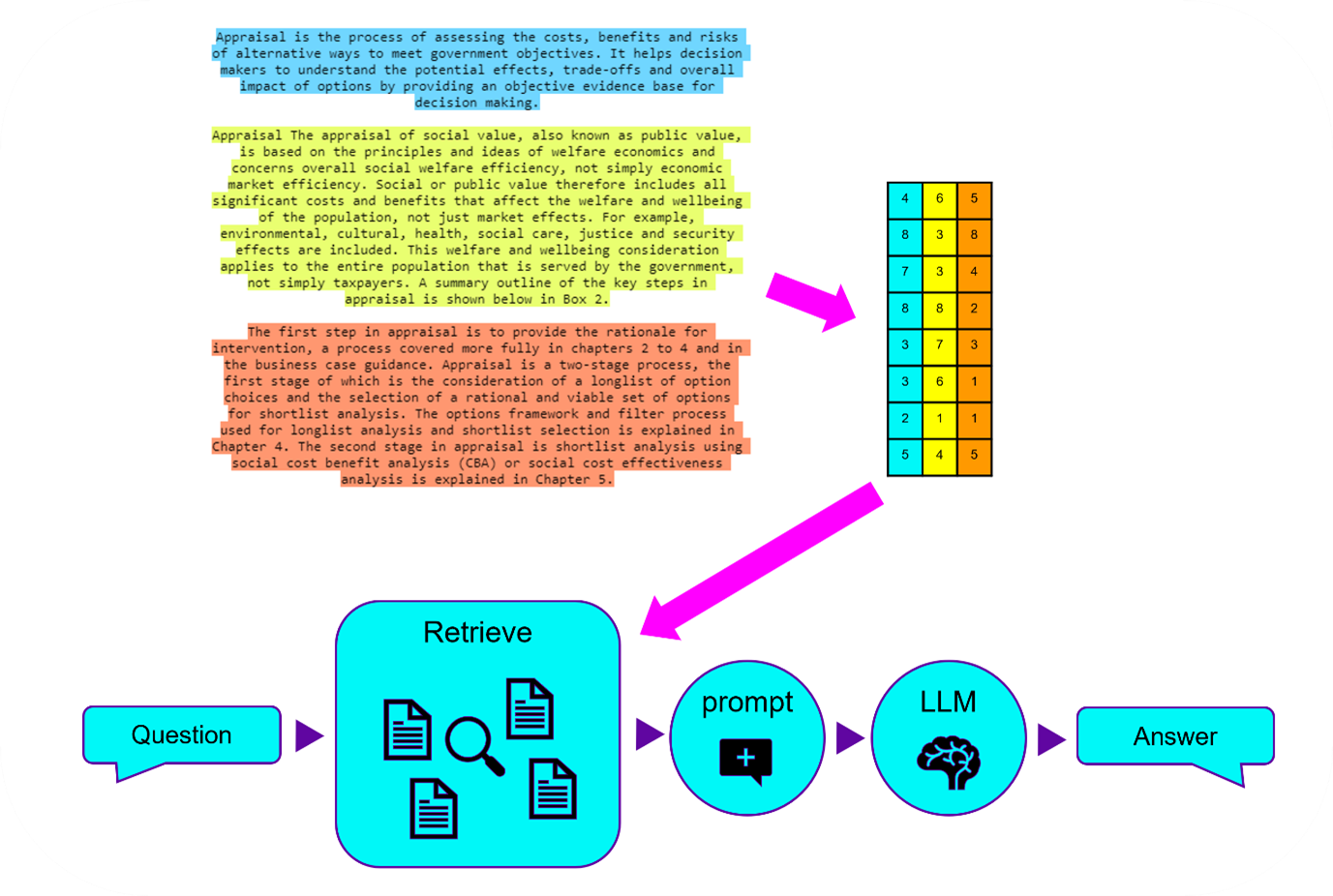

We always intended to build a Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) based solution to this problem. Back in spring 2024, this felt slightly more ground-breaking than it perhaps does now – but we’ve iterated a lot since then and made the solution robust.

RAG - from chunking, to vectorising, to storing, to the user flow of asking, retrieving and recieving.

RAG - from chunking, to vectorising, to storing, to the user flow of asking, retrieving and recieving.

We aimed at a “naïve”1 RAG process, which roughly looked like:

Chunking up the information in guidance documents and impact assessments

Creating a database of text and embedded vectors to represent those chunks

Allowing the user to ask a question, which is vectorised, and then the vector database is similarity-searched to serve up the topmost relevant chunks

Sending the question and the relevant chunks to an LLM endpoint and prompting for an answer befitting a professional economist assistant

Serving that answer, alongside the chunks and their original sources, to the user.

It was a key requirement from the start to show the user both the chunks retrieved and the sources that those chunks came from – that meant making sure we had solid meta information that could trace information back to its source on legislation.gov, or elsewhere, and that the user could simply click to be taken there and investigate further. As we iterated the project, this is something we prioritised in the UI to really showcase the ‘data findability’ requirement.

The vectorstore

As a proof of concept, the chatbot was originally built with local-friendly architecture; a Streamlit app run using a local FAISS vectorfile, and an API that linked to a personal ChatGPT account. This kind of set up was not at all suitable for a production-level app with potentially hundreds of users, however. For instance, FAISS is a good, local solution when you’re using <10 multi-page documents, but quickly becomes untenable with scale, as loading-in-memory is required for each launch.

After weighing up several options for vector storage—including Qdrant, Azure Cosmos DB, and Azure AI Search—we ultimately landed on Azure AI Search as the most practical and secure choice for our needs. While Qdrant offered a lower price point, it’s unclear security and the extra effort required to secure it within our Azure environment raised concerns. Azure AI Search, on the other hand, is an Azure-native solution, and so integrated better with our existing Azure setup, and was at least somewhat supported by Langchain RAG workflows. It also offered predictable monthly pricing within the S1 tier – though this turned out to actually be more annoying than helpful, because the tiering locks you in regardless of what your data size actually turns out to be, which you can only estimate before fully vectorising all of your documents. In our case, it turned out we only needed the Basic pricing tier (one below S1), which I only found out post-purchasing S1 and vectorising documents (in spite of doing my best to estimate rough size beforehand!) – though we were able to adjust to this tier later.

A huge part of RAG design comes down to how you chunk up your data – that’s going to determine how useful it is to your end users. Just a sentence, and you’re going to find things that are very specific, but your vectorisation costs will soar. A whole page, and you’re looking at more false-positives and for users to have to search through a bunch of unrelated info. Impact assessments are also somewhat homogenous in format, and it makes sense to present those to users in a way that makes use of their heading-and-subheading structure. We landed on using the package pymupdfLLM, the best of the bunch without using a visual encoder of some sort, and a hierarchical chunking process, with custom-designed recursive re-merging of chunks if semantically it made sense to.

flowchart TD

Start([Raw PDF Metadata + Markdown]) --> Clean["Clean Special Characters<br/>- Replace unicode bullets/dashes<br/>- Remove invalid UTF-8<br/>- Remove links"]

Clean --> HeaderSplit["Split by Markdown Headers<br/>(#, ##, ###)"]

HeaderSplit --> RecursiveSplit["Recursive Character Split<br/>Chunk size: 1500<br/>Overlap: 100"]

RecursiveSplit --> MergeLoop{Iterate & Merge Chunks}

MergeLoop --> CheckChunk[Check Each Chunk]

CheckChunk --> Condition1{"Is chunk < 500 chars<br/>OR starts with pipe?"}

Condition1 -->|Yes| MergeAction["Merge with<br/>Adjacent Chunk"]

Condition1 -->|No| KeepChunk[Keep Chunk]

MergeAction --> UpdateCount[Update Chunk Count]

KeepChunk --> UpdateCount

UpdateCount --> StableCheck{"Chunk count<br/>changed?"}

StableCheck -->|Yes| MergeLoop

StableCheck -->|No| PostProcess[Post-Processing]

PostProcess --> AddNewlines["Add newlines before/after<br/>table pipes"]

AddNewlines --> AddMetadata["Add Chunk Numbers<br/>& Document Metadata"]

AddMetadata --> Final([Final Chunked Documents<br/>with Metadata])

style Start fill:#e1f5ff,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px,color:#000

style Final fill:#d4edda,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px,color:#000

style MergeLoop fill:#fff3cd,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px,color:#000

style Condition1 fill:#fff3cd,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px,color:#000

style StableCheck fill:#fff3cd,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px,color:#000

A mermaid diagram showing the logic flow of document chunking in our process.

We used the latest (cost-optimised) Azure OpenAI endpoints for vectorisation and for the LLM part of the process. One well-known challenge with using API models is that these can be deprecated and otherwise altered under-the-hood without any notice – something that we fully came up against when we noticed a degradation in the chatbot’s performance that we couldn’t explain with prompt design or RAG changes, but which was very stark in our RAGAS results. It’s very hard to prove conclusively, but we’re pretty sure a change in the underlying model prompting resulted in a worse performance – luckily, we were about to change the model anyway, but this certainly informed my own caution in using API models in the future.

The full RAG pipeline was implemented using Langchain, and specifically a mixture of methods from Langchain versions 2 and 3. When we started using Langchain, we knew it might get messy – but at the same time, there wasn’t a very viable alternative. A year later, we have the benefit of hindsight, and wouldn’t advocate the use of what is really a very poorly documented framework – we’ve spent hours banging our heads on how to create vectorstore objects that support Azure AI Search fully, how to create context-awareness, how we might include smarter conversational history elements – frustrated by the lack of change management and accompanying documentation for Langchain versions.

In addition to the RAG chain itself, we had to build a class to interface between the RAG pipeline and the UI. This was because we needed to do things like store sources from responses beyond just one response ago – that is, we needed historical source caching, so that these sources could be shown in the UI regardless of where in the conversation the user was, and to offer them the ability to download their conversation for later use.

Beyond the naïve RAG, at the end of the project, we were also able to add in some additional functionality to focus the chatbot only on certain documents. It involved a lot of wrangling with a fixed-in-time version of Langchain, interacting directly with the Azure AI Search python SDK, but we successfully implemented the user interface and functionality to filter documents by year and document type. Doing so means that the chatbot will only compare the user question to the subset of documents they’ve specified via a range dropdown and checklist options. This was a really important development, because the vectorstore includes documents from throughout the last decade, over which guidance has been updated – the filters allow users to assert control over, for instance, seeing only the latest advice and implementations.